THE BATTLE OF ST. LOUIS AND ATTACK ON CAHOKIA MAY 26, 1780

By Stephen L. Kling, Jr., Esq.

Chapters

– BACKGROUND

– THE BRITISH ORGANIZE AN ATTACK FORCE

– PROVISIONS AND DELAYS

– THE BRITISH ARRIVE NEAR ST. LOUIS AND CAHOKIA

– STATE OF DEFENSE AT ST. LOUIS AND CAHOKIA

– THE BATTLE OF ST. LOUIS

– THE ATTACK ON CAHOKIA

– THE RETREAT

– THE PURSUIT

Background

After their defeat in the west at the hands of George Rogers Clark in 1778, the British belatedly realized the importance of this theater of war. The subsequent Spanish entry into the war opened up a whole new front in the west. Lord George Sackville Germain, the British Colonial Secretary for North America and de facto commander in chief for that theater, issued a series of orders to not only take back the American conquest but to conquer Spanish Louisiana as well. On June 17, 1779, orders were sent to Governor Frederick Haldimand in Canada instructing him to organize an attack from the north on the Spanish and Americans in the west. Haldimand in turn sent the orders to his lieutenant governors and commanders at the major northwestern forts at Niagara, Detroit and Michilimackinac. Niagara was too far away to provide active support for an attack along the Mississippi River, but the main attack force would be organized from Michilimackinac with supporting and diversionary attacks from Detroit. On June 25, 1779, Germain sent orders to General Campbell at Pensacola to attack Spanish Louisiana territory possessions from the south, starting at New Orleans and proceeding up the Mississippi River to link with the forces attacking from the north at Natchez.

Campbell’s planned attack was frustrated by the pre-emptive campaign of Bernardo de Gálvez. In fact, Gálvez had practically captured all of the British Mississippi River towns before Campbell had assembled his force for a strike on New Orleans. However, word of this failure of the British southern attack would not reach the British northern posts for several months, long after the campaign in the north was finished. The main attack from the north was organized at Prairie du Chien along the Mississippi River. Prairie du Chien was an ideal location for assembly and served as an annual trading ground for the Native Americans, British and local French traders.

The British Organize an Attack Force

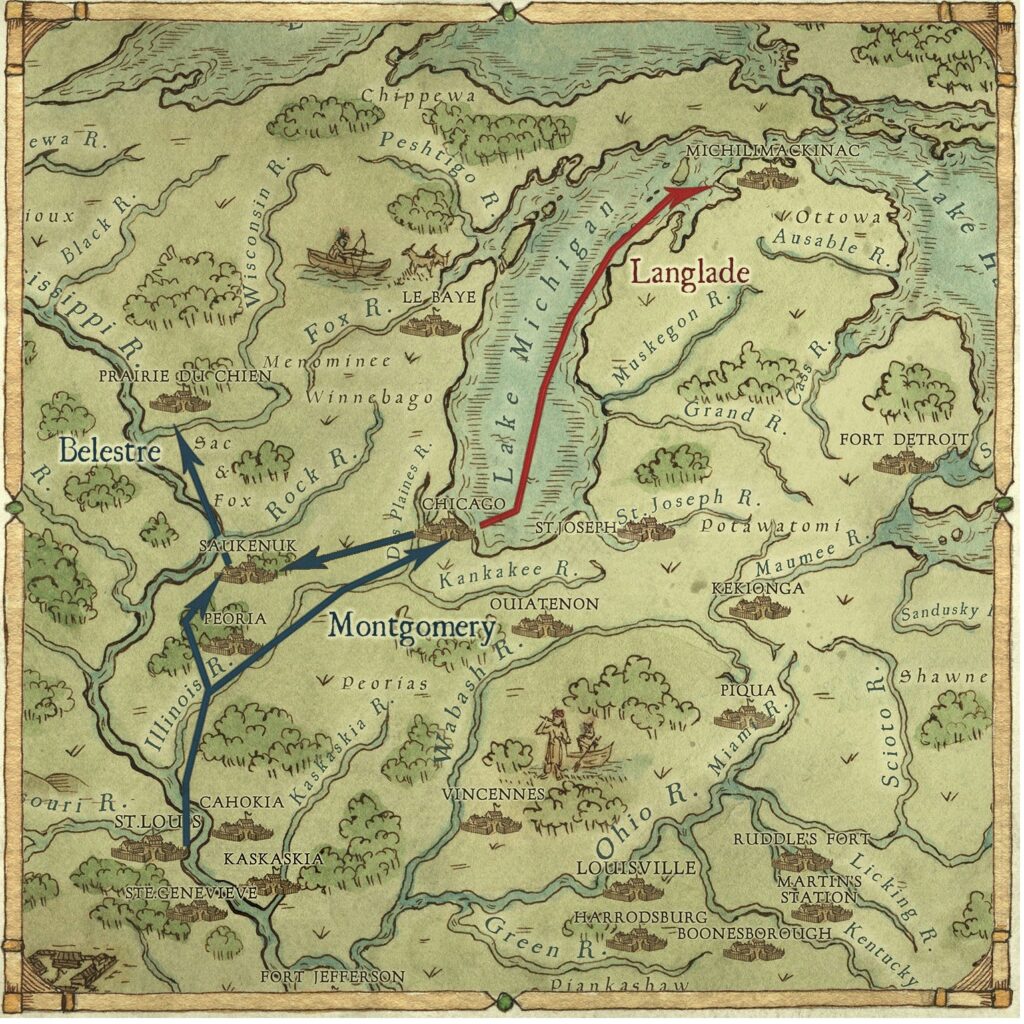

The northern British attack force was commanded by Captain Emmanuel Hesse, a former British army officer in the 60th Royal American Regiment turned fur trader. He would be supported by almost all of the British officers and interpreters in the British Northern Indian Department post at Michilimackinac. An additional fifty or so British Canadian traders and adventurers would join the expedition. However, the bulk of the attack force would be formed by British allied Native Americans: Chippewa (Ojibwa), Eastern Sioux (Dakota), Winnebago (Ho-Chunk), Menominee and a few other smaller groups. On their way south down the Mississippi River, they stopped at the main Sac and Fox village of Saukenuk, coercing a few hundred of their warriors to join them. When the attack force headed south from Saukenuk, the little army totaled around one thousand men and would have required hundreds of canoes. The objective of this force was Spanish-controlled St. Louis and American-held Cahokia, both rumored to be completely undefended.

The attackers were to be directly supported by another force, which moved down the Illinois River from the present-day Chicago area to meet up at St. Louis. This force was led by British Northern Indian Department personnel Captain Charles de Langlade and official interpreter Charles Gautier. While a few British Canadian traders were in their midst, this force too was comprised mostly of Native American warriors. Langlade’s orders instructed him to remain with his men in the area until after Ste. Geneviève and Kaskaskia were captured. Fortunately for the Spanish and the Americans, Langlade’s force got a late start and was delayed by the western branch of the Potawatomi who were centered around present day Milwaukee and were friendly to the Spanish and Americans.

The chief of the western branch of the Potawatomi was Siggenauk (Blackbird) who also was given the French name of Letourneau. He had met George Rogers Clark a few years before and maintained friendly relations with Americans. He also had a trading relationship with the Spanish. After his contribution in preventing Langlade’s men from joining the main attack and assisting the Spanish in a later raid on Fort St. Joseph, the Spanish awarded Siggenauk a silver and gilt sword in recognition of his services.

While the traders were induced to join the expedition on the promise of exclusive trading rights in the soon to be conquered Spanish territory, the Native Americans in the attack force were promised plunder. The chiefs of the two main tribes in Hesse’s attack force, Wapasha (Sioux) and Matchekewis (Chippewa), were commissioned as war captains by the British Northern Indian Department. They were issued British red coats and silver officer gorgets to signify their importance and authority as leaders of the expedition. The red coats were adorned with braid and epaulettes and the silver gorgets bore the arms of Great Britain and were hung around the neck with a decorative ribbon.

The British also supplied the Native Americans with substantial quantities of “presents:” muskets, gunpowder, flints, blankets, needles, mirrors, tomahawks and other assorted items to aid in keeping the Native Americans firmly joined with the British cause. The quality of the muskets and clothing indicated the status of the chief in both the eyes of the British military and the Native Americans. The allegiance these presents bought was fickle, with the Native Americans often acting according to their own best interests rather than those of the British cause, depending on where they saw their own advantage. But the well-equipped British Northern Indian Department was able to supply far more presents than the Americans or Spanish, and so most tribes in the West remained allied to the British cause during the war.

Provisions and Delays

The British attack force’s departure was delayed because provisioning proceeded slowly. However, British Lieutenant Alexander Kay and some Menominee scouts captured by chance a large flatboat loaded with trade goods owned by Charles Gratiot. As the pilot only had Spanish and American passes, the decision was quickly made to confiscate all of the cargo and imprison the pilot and his crew. This fortuitous event allowed the British to depart within days after the capture.

Curiously, while some men of the Royal Artillery and several cannons were at Michilimackinac, no artillery was taken along on the expedition. Further, some British regulars of the 8th Regiment of Foot helped organize the expedition at Prairie du Chien but none of them accompanied the attack force when it departed. This was likely due to the belief that St. Louis and Cahokia were defenseless and advanced tactics organized by experienced soldiers were not anticipated to be necessary. These decisions would prove costly for the British.

The British Arrive at St. Louis and Cahokia

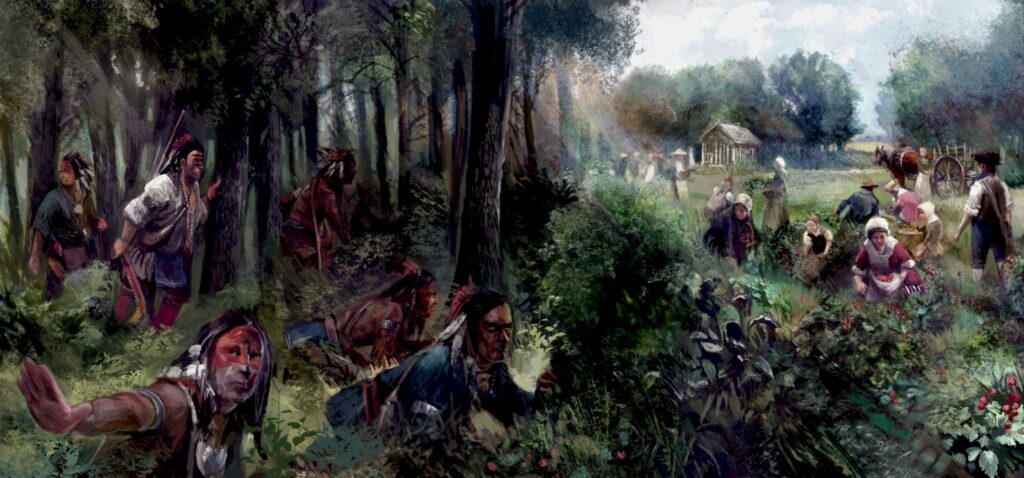

The British attack force arrived about 20 miles north of St. Louis and set up camp. From there they hoped to join up with Langlade’s force, and they used the opportunity to send scouts to St. Louis. Fortunately for the inhabitants of St. Louis, it was the Feast of the Corpus Christi, and many inhabitants were out in the fields picking strawberries and flowers. This activity prevented the scouts from getting close enough to St. Louis to see the defenses. This story comes from the recollections of Elizabeth Barada Ortes, who was sixteen at the time of the attack and lived to be 104.

Frustrated at their inability to obtain intelligence about St. Louis and unable to wait for Langlade due to a lack of supplies, the attack was planned for May 26, 1780. About 750 men would attack St. Louis while the remaining approximately 250 men would attack Cahokia. The plan was to land their canoes upriver traveling through the woods to surprise each town.

State of Defense at St. Louis and Cahokia

St. Louis and Cahokia were virtually undefended at the time the British planned their attacks. However, thanks to valuable intelligence received from Madame Honoré, Pierre Prevost, John Conn, a man named Fontaine and others, they had six weeks advance warning. Lt. Governor Fernando de Leyba, a person with extensive military experience who was also a captain of the Fixed Infantry Regiment of Louisiana, was in charge at St. Louis. Leyba commanded only a handful of Spanish regular soldiers and two companies of militia at St. Louis: one of infantry and a smaller one of cavalry. He also summoned a further sixty militia from Ste. Geneviève.

Under Spanish regulations, the militia was required to attend training in wheeling and firing by the local Fixed Infantry Regiment of Louisiana officers. Generally training was conducted on Sundays after Mass. Many of the militia were hunters and traders (men experienced with muskets), and several were former French army soldiers who elected to stay in the area after the end of the French and Indian War. Leyba’s plan for the defense of St. Louis included the construction of a large stone tower in the town’s center along the western boundary plus two thousand yards of entrenchments around St. Louis connecting the tower and the Mississippi River.

The site of the tower is near present day Ballpark Village in downtown St. Louis where it had a commanding view of the town in 1780. The tower was christened “Fort San Carlos” on April 17, 1780 by the local priest, Father Bernard de Limpach, and work began the same day.

Five cannon were secured and mounted in the tower, and smaller 2-pounder cannon and swivel guns were distributed amongst the defenders of the entrenchments. All in all, Leyba had 310 armed men under his command, most of whom were militia.

Across the Mississippi River at Cahokia, similar defensive plans were developed. The local militia under Commandant François Trottier were called out and a small company of Clark’s Illinois Regiment of Virginia began the repair of a large stone building at the mission property newly named Fort Bowman, which would be the lynchpin of the defense and sanctuary for noncombatants. Clark himself, with most of the rest of the regiment, was summoned from Fort Jefferson and arrived a few days before the attack. Thankfully Clark and Leyba were able to meet and to discuss strategy.

The Battle of St. Louis

There was other activity in and around St. Louis besides strawberry and flower picking that hindered the British efforts to obtain intelligence. Cavalry pickets were established in a perimeter outside of St. Louis to give warning of any attack. Large canoes also patrolled the Mississippi River bank near St. Louis and some smaller canoes were sent farther upriver to scout for the expected British attack. All of these events frustrated attempts to reconnoiter St. Louis, and the British scouts returned with little information about the town’s defenses.

Despite this, British leadership were confident in their strategy and numbers, and decided to attack the next day rather than wait for Langlade. 750 men, mostly Sioux, Sac and Fox warriors, would attack St. Louis while the rest, mostly Chippewa, would attack Cahokia. The attacks were intended to be simultaneous to prevent either town from aiding the other, but as the attackers of Cahokia had to paddle their canoes past St. Louis first, it is likely their attack started a little later than the one at St. Louis.

At 1:00 pm on May 26, 1780, the attack against St. Louis began. Laurent Reed, posted in Michael Lami’s barn on Barn Hill, shouted a warning; a cannon was fired from Fort San Carlos; a man ran through the town shouting “to Arms!” and the church bell rang out. Leyba’s men had pre-arranged stations along the entrenchments and rushed to man their positions. Afterwards Leyba wrote that not a single man remained in his home. Although critically ill, Leyba was carted to the tower and took command at the top, directing cannon fire.

As the attack against St. Louis unfolded, the British-led forces rushed the entrenchment line looking for a way into St. Louis. However, they were met with a hail of musket fire and the thunderous boom of cannon from the tower. The tower cannon likely caused few casualties, but the psychological effect was significant. Madame Rigauche donned her husband’s militia coat and took a position at the main gate, urging the defenders to hold. Some accounts later credited her with single-handedly saving St. Louis. Free black inhabitants in the town also contributed to the defense; these likely included local gunsmith Pierre Ignace dit Valentin. After two hours, unable to breach the defending lines, the attacking Sac and Fox unexpectedly fell back, and the rest of the force soon retreated.

Several St. Louis inhabitants had the misfortune to be out tending their fields when the attack began. Despite their cries for help, Leyba knew that any rescue efforts would leave his thin lines vulnerable to breach by the attackers and refused. It was these inhabitants who constituted most of the casualties. However, a few were lucky enough to make it back to the safety of the town after some daring exploits despite the constant fire of the British attackers. After the battle, Leyba tallied the casualties suffered during the attack: twenty-one dead, six wounded, and twenty-five prisoners. A further forty-six people were captured along the Mississippi River before and after the attack. Twenty cows and thirty horses were also lost.

The Attack on Cahokia

A similar story unfolded at Cahokia where the British attackers surged across the Rigolet Stream to attack that town. Makeshift defenses centering on the mission property blunted any attempt to penetrate into the town’s center. The defenders had a field cannon, which greatly aided their defense. The attackers made several attempts to draw out the defenders but every effort failed. With Clark’s reinforcements, the militia and a friendly group of around forty-five Kaskaskia warriors, the defenders must have numbered around 200-250 men, enough to hold Cahokia. After the attack, the British reported four killed and five prisoners at Cahokia but no wounded. However, an American medical requisition the day after the attack reflects a large medical bill, which indicates there were actually several wounded.

The Retreat

As both attacks were successfully repelled, the British forces retreated upstream with about seventy prisoners they had captured, destroying crops and killing livestock along the way. The combined defenses as well as the presence of “Big Knife” Clark and the unexpected cannon booming from Fort San Carlos, which the Native American attackers would later name the “House of Thunder,” thwarted the British attempt at conquest. After several days, scouts were sent out by both towns to confirm the British had left.

The Pursuit

The Americans and Spanish soon assembled a pursuit force. Due to the lack of supplies, the British split into several groups as they retreated northward. A mounted force of St. Louis militia cavalry, Roger’s Light Dragoons and Cahokia militia pursued the British group with the bulk of the captives up the Illinois River. They barely missed catching them near present-day Chicago according to a report by British Lt. Governor Patrick Sinclair. The remaining Americans and Spanish pursued another British group up the Mississippi River. They paused at the main Sac and Fox village at Saukenuk and were joined there by the mounted force moving down the Great Sauk Trail from the Chicago area. The village was abandoned but the Americans and Spanish burned all of the houses and destroyed all of the crops. The overzealous destruction resulted in a food shortage which was only remedied by the butchering of several valuable cavalry horses which Captain Rogers complained bitterly about in a later letter to George Rogers Clark. A note was also left in a bottle hanging from a tree promising a return next spring. The note had its effect: the Sac and Fox chiefs came down to St. Louis, surrendered their British peace medals and British flags, and accepted Spanish ones to signify their change of allegiance.

Some prisoners in the custody of the Sac and Fox were returned to St. Louis as a gesture of good faith. Several local French traders were also able to secure the release of prisoners in the months following the attack. By the war’s end, most prisoners had been released.

Watch the “House of Thunder” Video on YouTube

References and Links

For further reading or learning:

The American Revolutionary War in the West, edited by Stephen L. Kling, Jr.: https://www.amazon.com/American-Revolutionary-War-West/dp/099645571X.

Cavalry in the Wilderness, by Stephen L. Kling, Jr.: https://www.amazon.com/Cavalry-Wilderness-Western-American-Revolutionary/dp/0996455744.

House of Thunder DVD, awarding winning documentary on the Battle of St. Louis by HEC Media: https://www.thgcpublishing.com/house-of-thunder.

Battle of St. Louis and Gálvez’s Mississippi River Campaign Puzzles: https://www.thgcpublishing.com/puzzles.

Road to Independence, Battle of St. Louis, Attack on Cahokia and Battle of Baton Rouge Games all designed by Stephen L. Kling, Jr. : https://www.thgcpublishing.com/games-available-now.